Cryptocurrency is one of the most controversial yet imagination-stirring inventions in global finance over the past decade and a half. From a fledgling idea within cryptography circles and underground tech forums, cryptocurrencies have evolved into a global phenomenon that has forced central banks, governments, technology corporations, and investors to take notice. Yet after more than 15 years of existence, cryptocurrencies have still not delivered the payment revolution once widely expected. To understand why, it is necessary to retrace their origins, development, and collision with economic and social reality.

1. Historical background: when trust in traditional money eroded

Cryptocurrencies did not emerge in a vacuum. They were born in a very specific historical context: the 2008 global financial crisis. As major banks collapsed and governments injected trillions of dollars to rescue the financial system, public trust in central banks and fiat currencies was severely shaken.

To many observers, the traditional monetary system exposed three fundamental flaws. First, concentrated power: central banks can create money, adjust interest rates, and erode the value of citizens’ savings through inflation. Second, financial intermediaries: almost all transactions require banks or payment institutions, increasing costs, delays, and systemic risk. Third, limited global efficiency: cross-border transfers remain slow and expensive, especially for developing economies.

In this environment, a bold question began to take shape: could a form of money exist without banks, without government control, yet still remain secure and resistant to fraud?

2. The early ideas: from cypherpunks to the dream of decentralized money

Before cryptocurrencies officially appeared, many experiments had already been attempted. In the 1990s, the cypherpunk movement—a loose group of cryptographers, programmers, and libertarian activists—advocated using technology to protect individual privacy from states and large corporations. They believed cryptography was not merely a technical tool, but a political one.

Projects such as DigiCash, e-gold, and b-money attempted to create digital money but ultimately failed because they could not solve the “double-spending problem”: how to prevent a digital unit of value from being copied and spent multiple times without relying on a trusted intermediary.

The turning point came in 2008, when an individual (or group) under the pseudonym Satoshi Nakamoto published a short but revolutionary paper: Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System. The paper combined existing concepts—cryptography and peer-to-peer networks—with a novel mechanism for achieving consensus without intermediaries.

3. The birth of Bitcoin and the technological foundation

In January 2009, the first Bitcoin block—the Genesis Block—was mined. Embedded within it was the now-famous message: “The Times 03/Jan/2009 Chancellor on brink of second bailout for banks”—a clear political statement reflecting discontent with the existing financial system.

Bitcoin’s breakthrough rested on three core elements. The first was the blockchain, a distributed ledger in which transactions are recorded publicly and are nearly impossible to alter. The second was the Proof of Work consensus mechanism, which requires “miners” to expend computational energy to validate transactions, thereby securing the network. The third was scarcity: Bitcoin’s supply is capped at 21 million units, standing in stark contrast to fiat currencies that can be issued without limit.

At first, Bitcoin had virtually no value and circulated only among technology enthusiasts. Yet its simplicity, transparency, and resistance to censorship gradually attracted wider attention.

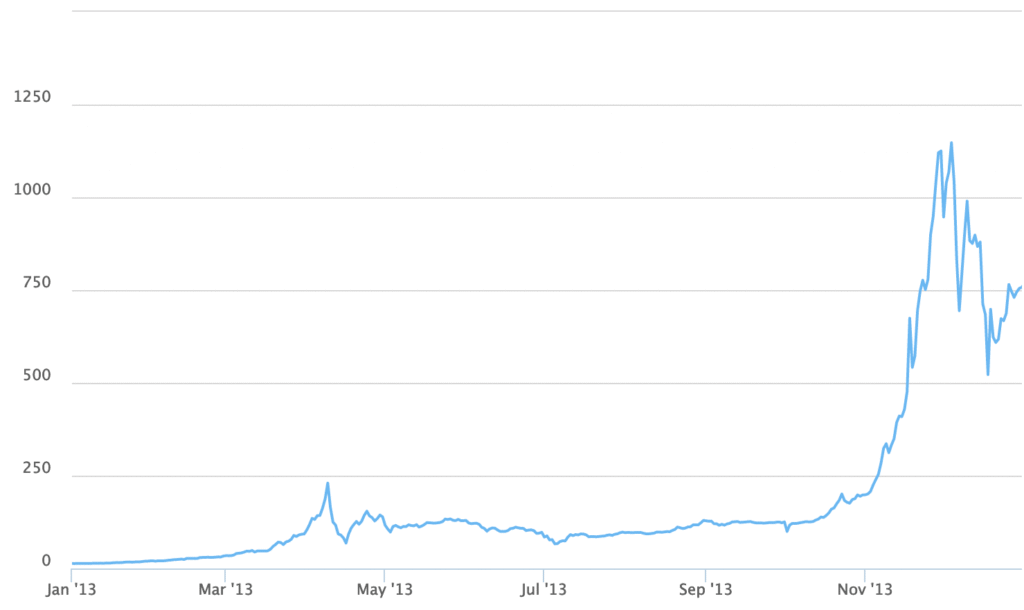

4. From technological experiment to speculative asset

A symbolic milestone in cryptocurrency history occurred in 2010, when 10,000 Bitcoins were used to buy two pizzas. At the time, few could have imagined that a single Bitcoin would later be valued at tens of thousands of dollars.

The period from 2013 to 2017 marked the first major boom. Bitcoin prices surged, followed by the emergence of thousands of alternative cryptocurrencies. Ethereum, launched in 2015, expanded the concept by introducing smart contracts, enabling programmable, self-executing agreements. From that point on, cryptocurrencies were no longer just “money,” but platforms for decentralized applications.

Alongside innovation, however, came speculation. Many participants entered the market not out of belief in decentralization, but in pursuit of quick profits. Cryptocurrencies increasingly resembled high-risk, highly volatile assets rather than stable means of exchange.

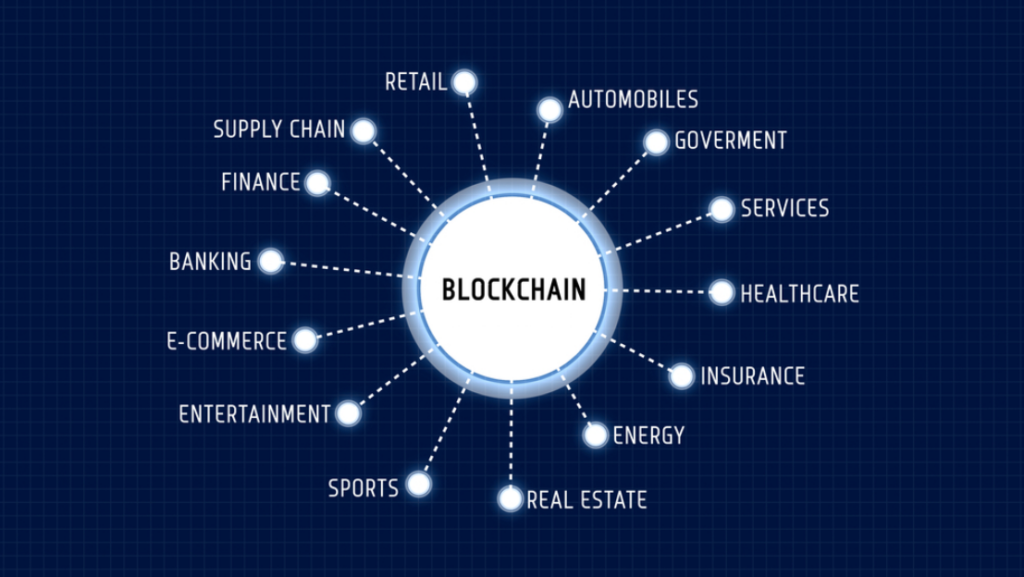

5. Applications in daily life and the economy

Although cryptocurrencies have not replaced fiat money, they have found niches across several domains.

In cross-border remittances, cryptocurrencies enable faster and cheaper transfers than traditional banking systems, especially in regions with weak financial infrastructure. For migrant workers, sending money home via cryptocurrencies can significantly reduce costs.

In decentralized finance (DeFi), users can lend, borrow, and trade assets without banks. This represents an ambitious experiment in reimagining financial architecture, though it carries substantial risks.

Cryptocurrencies have also enabled new models within the digital economy, such as NFTs in art, blockchain-based games, and Web3 ecosystems. In countries experiencing high inflation, cryptocurrencies are sometimes viewed as a hedge to preserve value.

6. The global boom and the entry of institutional capital

The years 2020–2021 marked the peak of global attention. The COVID-19 pandemic prompted unprecedented monetary easing by central banks, with record-low interest rates and abundant liquidity flowing into risky assets. Bitcoin was increasingly labeled “digital gold” by some investors.

Major technology firms and financial institutions began to participate. Companies like PayPal enabled cryptocurrency purchases, while investment funds launched Bitcoin-related products. Cryptocurrencies moved closer to the financial mainstream.

Yet this boom also exposed weaknesses: speculative bubbles, fraud, low-quality projects, and heavy dependence on market sentiment.

7. Why cryptocurrencies have not triggered a payment revolution

Despite their promise, cryptocurrencies have not become widely adopted payment instruments. Several interrelated factors explain this outcome.

First is price volatility. A functional payment medium must maintain relatively stable value. When prices can rise or fall by double-digit percentages in short periods, both merchants and consumers hesitate to use it.

Second is user experience. Wallets, private keys, transaction fees, and the risk of irreversible loss due to user error make cryptocurrencies far more complex than swiping a card or making a bank transfer.

Third are regulatory barriers. Governments worry that cryptocurrencies could facilitate money laundering, tax evasion, or financial instability. Inconsistent policies across jurisdictions make it difficult for businesses to integrate crypto payments.

Fourth are performance and environmental concerns. Some blockchain networks consume large amounts of energy and process transactions slowly, making them less competitive than highly optimized centralized payment systems.

Finally, social trust remains crucial. Most people trust fiat currencies not only because of law, but because of history, habit, and state backing. Cryptocurrencies, by contrast, require trust in code and communities—a leap many are still unwilling to take.

8. Failure or a different path?

Declaring cryptocurrencies a “failure” may be premature. Rather than replacing cash or bank cards, they are increasingly positioning themselves as a new asset class and an experimental infrastructure for financial and digital economic models.

Many central banks are now developing central bank digital currencies (CBDCs), borrowing from blockchain technology while retaining state control. This alone demonstrates the profound influence of cryptocurrency ideas, even if they have not unfolded exactly as early pioneers envisioned.

The emergence of cryptocurrencies was driven by a crisis of trust

The emergence of cryptocurrencies was driven by a crisis of trust, technological advancement, and a desire for financial autonomy. From a short white paper in 2008, cryptocurrencies have grown into a global ecosystem affecting finance, economics, and the very way societies think about money. Yet the gap between revolutionary ideals and practical reality remains significant.

Cryptocurrencies have not delivered the payment revolution once anticipated, but they have achieved something else: forcing the world to rethink the nature of money, financial power, and the role of technology in shaping the future of the global economy. And perhaps it is this journey—rather than the destination—that represents their greatest contribution.